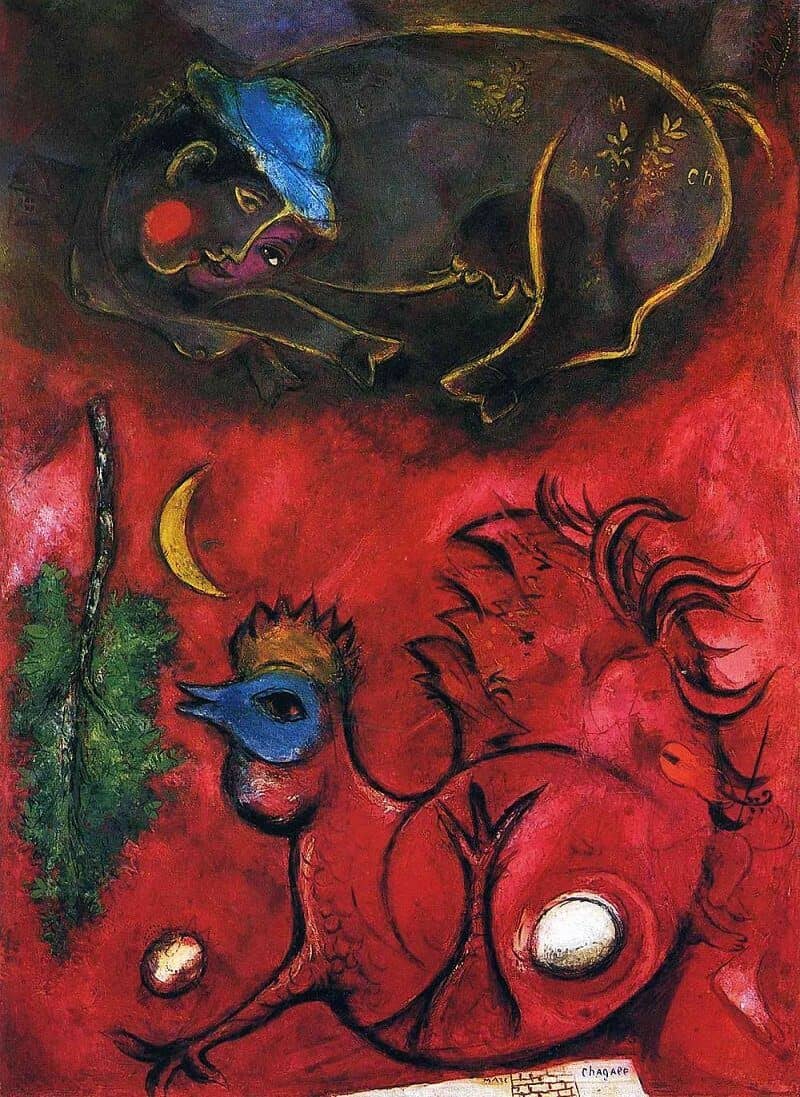

Listening to the Cock, 1944 by Marc Chagall

Listing to the Cock suggests one of the fundamental problems of Chagall's pictorial language: a tendency for motifs to acquire an independent existence of their own, which threatens to rob them of their expressive power.

Familiar elements in his work - all the loving couples, huts, animals, and later the religious images - are deployed in new combinations to determine the character of any given painting. Like words, they are strung together into

evernew sentences, yet the many repetitions deprive them of specific meaning. Their symbolic value as representatives of another reality in a picture is levelled out; instead they become quotations from Chagall's own ceuvre.

Parts of a seemingly mysterious world, they soon come to suggest nothing but their own exoticism, and the reality they are supposed to stand for becomes schematized.

Thus, in the end a Chagall painting will convey only a mood, a mood which depends far more on the use of colour than on exact content. The motifs merely serve a purpose of recognition, endowing the typical Chagall hallmark; and

in this way Chagall's initial aura of strangeness is dispelled. The uniquely formulated appeal for tolerance and understanding became in danger of being submerged in a welter of the merely typical, and it was only Chagall's dynamic

capacity for stylistic change that enabled him to keep this danger at arm's length. In this he shows himself to have been a diligent student of abstract painting: his brushstrokes and combinations of colours are the major

determinations of specific content and individuality in a Chagall painting, not the thematic motifs.

Listing to the Cock testify to this. The figure of the cockerel, distinguished from the red background only by its outline and the colourful head, incorporates two more of Chagall's exemplary motifs: the dainty position of

the legs recalls the athleticism of his acrobats, while a fiddler can be found tucked away in the cock's tail feathers. Wittily, Chagall has his cock ready to lay an egg, this image offering the same unison of male and female seen

in the cow against a black background, whose head turns out to be the faces of two lovers. The crescent moon, the tree standing on its head, and the hut round off this selection of Chagall's stock imagery. The ruddy dawn heralded

by the cock's crow is gradually dispelling night the province of the lovers, and this may suggest that the picture is to be read as a document of new hope, that gleam of hope Chagall felt as the collapse of Nazism approached.