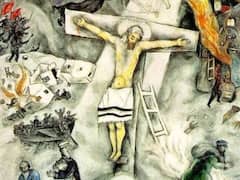

The Falling Angel, 1923-47 by Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall returned to Europe in 1946, arriving in Paris. In 1947, he finished The Falling Angel (1923-1947), which had been in the works for almost 25 years. Begun only a short time after Chagall's emigration from the Soviet Union, it is, in a way, a unified artistic statement for these years, expanded and built upon as Chagall's art developed. It combines Biblical and Torah lore with the modern world and with Chagall's personal symbolism in a juxtaposition of images that attempt to summarize the many experiences the artist had over the course of his work on the painting.

When he began it in 1922, with memories of the Russian revolution still fresh, the picture was to have included only the figures of the Jew and the angel and was meant as a representation of the Old Testament vindication of the presence of Evil in the world. Yet, in the years up to the painting's completion in 1947 the artist increasingly incorporated motifs reminiscent of his little Russian world, in the end even adding the Christian images of the Madonna and of Christ on the Cross. His Jewish vision, his personal life-story, and motifs of Christian redemption are incorporated into a programmatic statement that sums up Chagall's entire oeuvre. The images have been added one to another; in their totality, and in the diversity of their associations, they represent Chagall's unceasing endeavour to locate one single, truthful, universally valid visual formula. Its very history, its long journey halfway round the world, the whole generation required for its completion make this picture typical of twentieth century art, of the displacement and jeopardy that beset a work in its newly autonomous condition.

Its very history gave this picture that authority which Chagall had always aimed at and which was commensurate with the Jewish awe of images. His own odyssey, which ended happily with his final return to France in summer 1948, had from avery early stage, ever since Walden's Berlin exhibition, also been the odyssey of his work.

After the painting was exhibited, a change came over the artist. Chagall, who had spent so much of his life in large cities, socializing in the most forward-thinking of circles, expressed a wish to retreat from public life. In 1950, he moved to the quiet town of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat on the Mediterranean coast of France. Ironically, just as he thought to seclude himself, the Marc Chagall was rising to the height of his fame.